How "green" is Uber Green? 🌱

Exploring the company's push to incentivize EV adoption

This month, Uber announced that it was expanding its “Uber Green” option to 1,400+ cities across North America including D.C., Houston, Miami, and New York. For people living in these areas, you can request a ride the same way you normally would, the difference being now you get to choose whether you want someone in a gas-guzzling 2010 Ford sedan to pick you up via the cheapest (and most popular) option using UberX… OR select Uber Green and watch as a shiny Chevrolet Bolt rolls up curbside.

Uber Green is one of Uber’s “four key actions” aimed at reducing the company’s carbon footprint. In addition to this new ride option, the company has pledged $800 million to help its drivers transition to EVs by 2025, to invest in its “multimodal network” to promote cleaner mobility options, and be more transparent and accountable to the ride-hailing public. All of this is part of Uber’s push to become a “fully zero-emissions platform” by 2040, with an even more ambitious goal to have 100% of rides take place in EVs by 2030.

Given that electrification of the nation’s vehicle fleet is imperative if policymakers are serious about limiting global temperature increase to 1.5° Celsius, I wanted to focus specifically on Uber’s effort to electrify its own “fleet” of driver-partners.

How does Uber Green work?

As designed, Uber Green is a combination of push and pull forces that when combined are anticipated to spur EV adoption. Drivers who operate hybrid or electric vehicles can expect to earn an additional $0.50 per trip on Uber Green. For those drivers operating EVs, there is an additional “Zero Emissions Incentive” of $1.00 per trip. That incentive is then split 50-50, with half going to the driver and the other half to Uber’s “Green Future” program which (purportedly) helps drivers transition to EVs.

From the rider’s perspective, Uber Green is an environmentally friendly way of getting around town. Now, you can be chauffeured from Point A to Point B knowing that your trip is carbon-neutral and that you’re helping Uber invest in the future of transportation. As a sidebar: if you’re an Uber Rewards participant, you’re also eligible for 3x points for every eligible dollar spent on trips completed with this option. Most importantly though, you get to feel less bad about relying on point-to-point transit via the internal combustion engine (responsible for some ~30% of greenhouse gas emissions in the US).

The choice architecture of hailing a ride

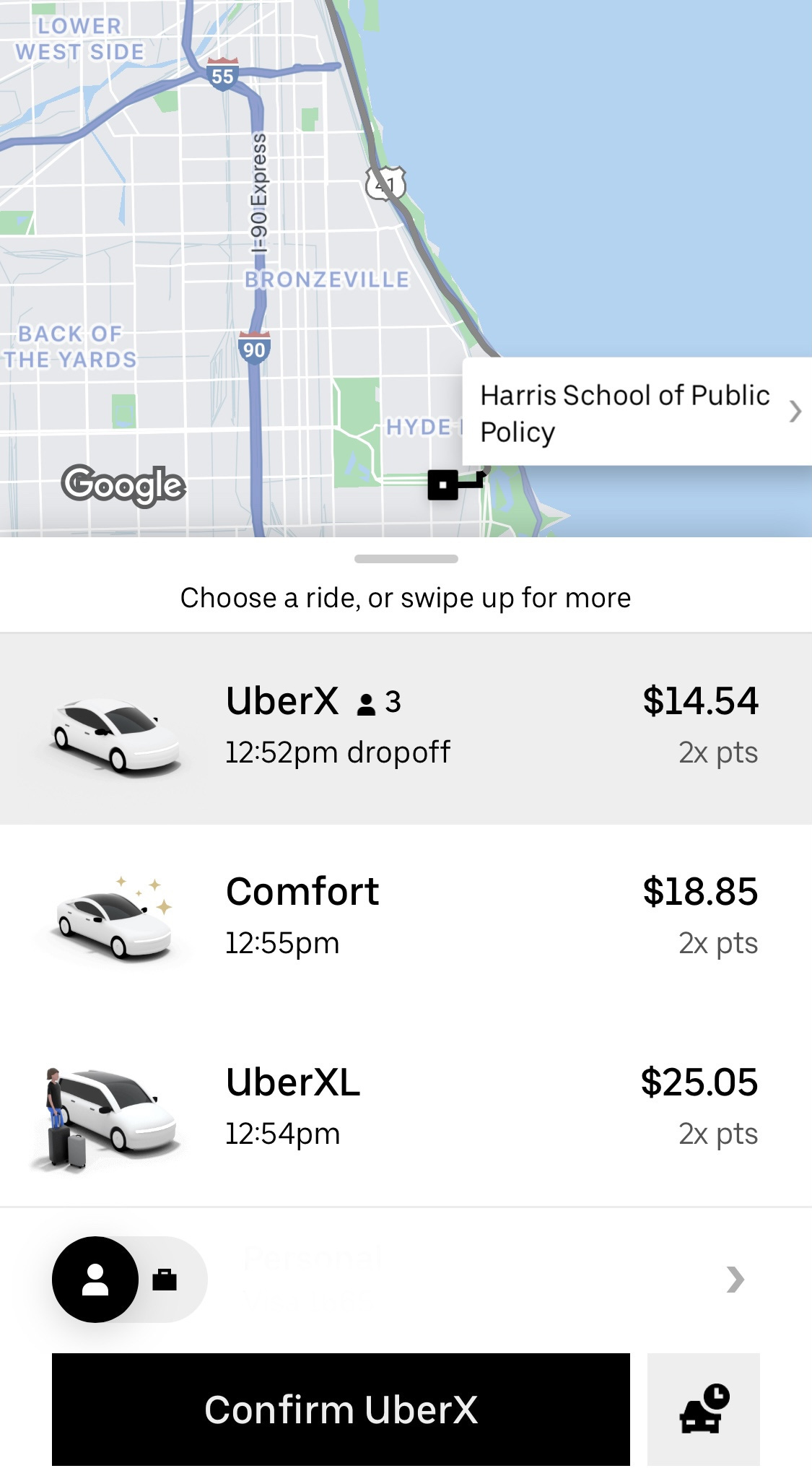

Just now, I pulled up my Uber app to request a hypothetical ride from the South Loop of Chicago to Hyde Park. (Not only is the ride hypothetical, but accessing my university’s facilities is too, as most of the campus remains closed due to Covid.) Despite the service now being operational in Chicago, Uber Green is nowhere to be found. Here’s a screenshot of my phone:

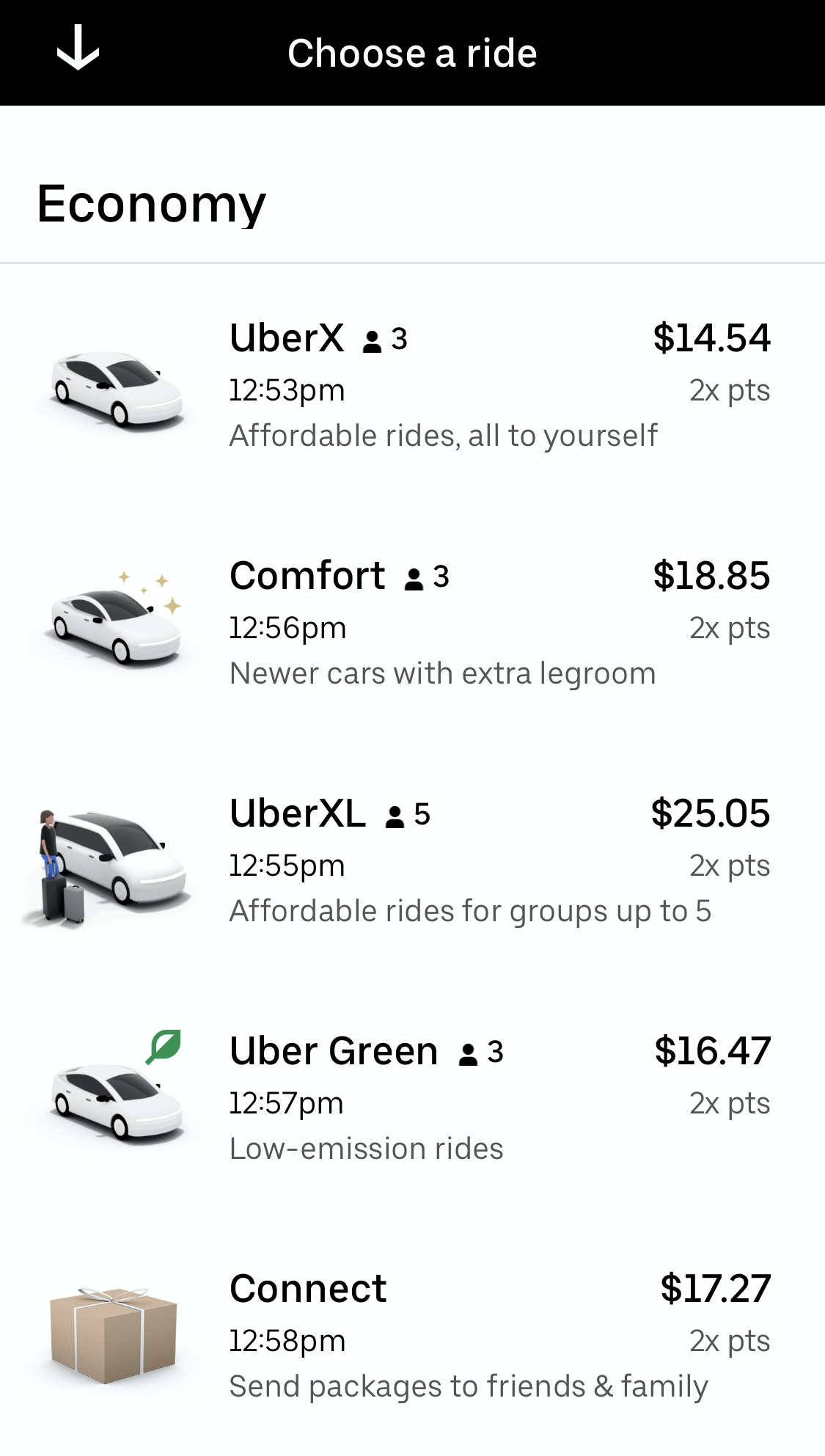

If Uber was serious about promoting this new cleaner option — one that is reasonably priced (at just $1.93 more than the UberX option) — then surely it would feature the option more prominently in its UI, right? Instead, Uber has elected to bury the Uber Green option just one place removed from the bottom of the list. Apparently, the only thing less important to Uber’s users is sending a package by courier:

What’s the big deal, you say? People just have to activate a thumb muscle to scroll down in order to browse all of their options.

The reason why this matters is simple: the ride-hailing public is mostly comprised of homo sapiens, the last time I checked. Decades of behavioral science and decision research strongly suggests the degree to which human beings are susceptible to cognitive biases, invisible boundaries and unconscious habits.

Cass Sunstein, a former Obama administration official, applied nudge theory to completely rethink how government forms and other paperwork are designed. It turns out that how a paper form is constructed — including things like placement, readability, and conciseness — alter the way in which someone fills it out.

A supporting analogue is voter ballots. We often think we are firmly in control of who we choose to represent us in government at the Federal, state and local levels. We believe that we are consciously choosing politicians based on their level of integrity, their understanding of the issues that affect us, and their stated policy preferences.

But this does not align with what happens in practice. Instead, our overconfidence blinds us to the positioning of candidate names. We fail to recognize how our eyes instinctively gravitate to those names at the top (and especially the first name) and how we barely notice those at the bottom.

If Uber truly cared about influencing user behavior to stoke higher usage of zero-emission rides, then why not place Uber Green one line below the slightly cheaper option UberX? This seems like an obvious UI fix, but instead Uber has elected to show riders its more expensive options with Comfort and UberXL. Worse yet, they are relying on its users to perform additional work to find out about this new option. This goes against what Uber founder Travis Kalanick once called the “frictionless” experience.

What are the barriers to EV adoption among TNC drivers?

Moving beyond these UI kinks, Uber faces a very steep climb when it comes to transitioning its driver-partners to electric vehicles. The Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) just published a briefing on what is required for TNCs to accelerate EV adoption.

As RMI notes, the ride-hailing industry represents a key lever in electrification since TNC drivers produce more emissions (3x as many miles per year as the average American motorist!). In addition, TNC fleets can serve as anchor tenants for high-speed public charging stations, which are sorely lacking across the continental US.

RMI’s report suggests that there are three major barriers to ride-hailing electrification:

Technological capability. Battery range, while improving at a rapid clip, is still not where it needs to be to entice more buyers to the showroom.

Financial competitiveness. The cost of ownership for EVs must be at least as good as, if not better than, the ICE vehicle it replaces. This includes access to reasonably priced fast-charging infrastructure. RMI predicts that at best the total cost of ownership (TCO) for EVs won’t hit parity with ICEs until 2025 (and that’s only with fleet discounted prices for EV charging rates).

Charging infrastructure. “Range anxiety” is what current EV owners (as well as prospective EV buyers) experience when they worry about being stranded in a charging desert. Most TNC drivers live in areas where public charging infrastructure is abysmal. These drivers rack up high daily mileage and don’t have the luxury of parking their EV in their own garage.

Obviously, Uber does not have much influence over point #1. Battery manufacturers, including companies like Tesla, will continue to innovate in this domain. Ride-hailing companies like Uber can only wait patiently for the battery revolution to arrive courtesy of Elon’s engineers in Nevada.

In the meantime, however, Uber can add value on points #2 and #3, for example by reducing the costs of public charging infrastructure through fleet-rate discounts and working with EV manufacturers to offer incentives (rebates) for new vehicle purchases, again using its scale to extract price concessions.

Here, Uber has already made some strides. For example, Uber has partnered with EVGo to offer 25% savings on EVGo Fast Charging stations’ standard rates (note this requires drivers to sign up for Uber Pro Gold, Platinum, or Diamond). Additionally, it offers a $125 discount on Enel X home charging kits; these are 240-volt Level 2 chargers which can provide most EVs with a full charge in 3-4 hours. Finally, eligible Uber drivers can receive up to ~$2,800 off the MSRP on select 2021 Chevrolet Bolt EV Premier vehicles. Importantly, this offer does not apply to buyers that require special financing or who want to lease an EV.

Even with all of these sweeteners, a Chevy Bolt buying bonanza is a fantasy. EVs remain far more expensive than conventional gas-powered vehicles: the average small car costs roughly $20k while the all-electric Bolt costs at least $10k more. More importantly, EVs remain completely out of reach for a large chunk of TNC drivers who work multiple part-time jobs just to survive.

Then there’s the additional point that many TNC drivers lease or finance their vehicles (which is why many drivers wouldn’t qualify for the Bolt discount to begin with). The current pricing structure of EVs simply does not align with the purchasing power of the TNC workforce who by nature of their independent contractor status lack the means to access this (still) premium product.

Is there anything Uber can do to accelerate EV adoption?

Uber thus finds itself in the odd position of championing electrification of “its” vehicle fleet when in reality it exerts very little control over that part of its business. We mustn’t forget that Uber is ever-cautious of making moves that would give regulators an avenue for interpreting their drivers as employees. Sure, the company is happy to offer incentives to nudge their drivers towards EVs, but Uber will not go as far as purchasing company-owned vehicles (otherwise the “driver-partner” relationship melts away).

Something Uber might consider is a franchise model. This is not as far-fetched as its sounds; when California moved to classify TNC drivers as employees under AB-5, the company reportedly considered licensing its brand to independent operators. Under a “fleet model”, Uber could license its technology platform to fleet operators willing to lay down the upfront capital to purchase EVs. A fleet model would align with Uber’s historical practice of de-risking, in this case by avoiding the capital costs of electrification.

There’s the added benefit of not having rapidly depreciating assets on your balance sheet, since future iterations of battery tech will swiftly replace outdated EV models. (It’s ironic writing this because Uber is also the company responsible for sticking a knife in the side of the black-car livery business). Obviously, moving to a franchise model would require a fundamental realignment of Uber’s business, which may be enough to give it pause.

Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi once said he’d like to see his company become the “Amazon of transportation”. Perhaps Khosrowshahi could borrow a page from Bezos’s Everything Store, and go long on infrastructure: instead of warehouses, build EV charging stations. This too will seem odd and incongruous with Uber’s two-sided marketplace. Isn’t that the job of policymakers?

But just to stretch the thought experiment a bit further: what if Uber had, instead of betting on autonomous vehicles or flying cars, poured money into EV charging infrastructure? When you recall that the unit economics of urban car service are really quite poor, you can see why this hasn’t happened yet. While fully autonomous ride-hailing (whenever it arrives) could have made Uber a profitable company, helping drivers reduce their carbon footprint isn’t going to juice Uber’s stock.

In the meantime, it seems fair to say that Uber is comfortable letting someone else pay for our green future.