Does Prop 22 change everything?

Hint: Don't believe the hype

Tucked within the results of a seemingly never-ending Election Day was a state-level ballot initiative that sought to carve out a new labor classification. California’s Proposition 22 (“Prop 22”), while not nearly as consequential for that state’s finances as another referendum on the ballot, was unprecedented in the sense that it was labor law written expressly for a single industry (and what some could argue a select handful of companies).

Personally, I’ve never bought into the notion of the “gig economy” as it’s just a stylized version of anything that qualifies as informal labor. The companies which fall under this nebulous category are those technology upstarts that offer jobs-for-hire and excel at branding (i.e., ride-hailing companies like Uber/Lyft, food delivery companies like DoorDash and Grubhub, as well as handyman apps like TaskRabbit).

Prop 22 focused exclusively on app-based transportation workers (ride-hailing) and couriers (food/goods delivery); as written, the referendum will primarily provide a “minimum earnings guarantee” (~120 percent of the CA minimum wage), a healthcare stipend allocated on the basis of hours worked, and require companies to provide accident insurance in cases of injury.

Source: New York Times

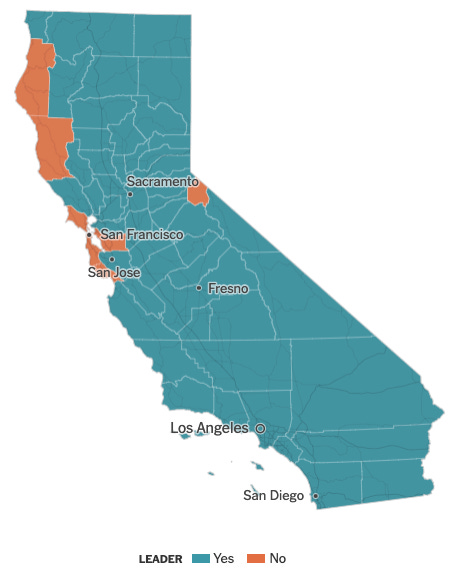

On E-Day, California voters approved Prop 22 by an overwhelming margin, with nearly 60% of voters saying “Yes”. Tellingly, the referendum received broad support across geographies and demographics. With the exception of liberal-leaning enclaves like the Bay Area and West L.A., most voters in the state did not see a compelling reason to vote against the industry-led initiative.

In the days which followed, many commentators attributed the end result to the companies spending hundreds of millions of dollars on political advertising and messaging campaigns. At least $200 million in “Yes on 22” ads was traceable back to Uber, Lyft, DoorDash and the like. Untold amounts more were spent on contracting PR teams, freelance “journalists”, and political operatives to sway undecided voters.

The Play: Regulatory Arbitrage

The mainstream press — in a spectacular example of groupthink — jumped on the train of “this will surely serve as a model law for the rest of the country”, basically regurgitating the companies’ press releases. However, there is nothing which would suggest this is true; although there are implications. With respect to the ride-hailing industry, California is certainly a bellwether state. After all, it was the Golden State that first defined companies like Uber and Lyft as transportation network companies or “TNCs”.

Following a series of awkward regulatory battles at the local level (most notably in San Francisco), the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) formalized the rules in 2013. Today, companies like Uber rely heavily on that classification, frequently invoking their status as nothing more than a “technology platform” or a two-sided marketplace that matches riders with drivers (that is, Bill Gurley’s favorite kind of investment).

Here at the start of 2021, we are far removed from the days of “UberCab”. There was a time not that long ago when government officials were completely frazzled by the arrival of ride-hailing services (How do we regulate this? Is there anything on the books which makes this illegal?). Back then, city officials were slapping companies with “cease and desist” orders only to be completely gamed by more clever software engineers (Greyball being the most infamous example).

Today however, regulators are far more familiar with the companies’ technologies and their associated impacts on local labor markets. Cities like Seattle, New York, and Chicago have moved to formalize rules on ride-hailing within their jurisdictions. Some of the more ambitious (sophisticated?) cities have even implemented minimum earnings formulas which serve as a kind of wage floor.

On paper at least, Prop 22 seems to do just that: provide a floor on wages and a stipend to help pay for health insurance. However, a key stipulation of the ballot initiative requires that the benefits only apply during periods of time when workers are “engaged” on the app (i.e., picking up/dropping off a passenger or en route to deliver your cold burger). This should not come as a surprise since the referendum was written by the companies that the law purportedly regulates. The reason why this is so consequential is that the companies retain ultimate control over that metric: “engaged” time.

For example, there is nothing which prevents Uber (or Lyft) from deciding that once a driver bumps up against the 25 hours worked during a week mark (i.e., when the 82% healthcare subsidy kicks in) the number of trip requests that driver receives suddenly drops. If this sounds dramatic, consider the fact that for years drivers have complained of sudden (and inexplicable) deactivations or reduced trips once having received a “bad rating”.

Uber et al. went to extraordinary efforts to get Prop 22 passed because they know it’s a state-level template for retaining control over their “driver-partners”. In the eyes of Uber/Lyft, state law is considered king because it usually preempts local rule-making and, as Veena Dubal notes, usually conforms to the companies’ policy preferences. Importantly, Prop 22 will enable Uber/Lyft to continue to assert quasi-monopolistic pricing power in that market. It’s way better than New York City’s TNC rules which mandate some of the strictest data-sharing requirements in the country and it’s still better than Seattle’s law because there is no utilization requirement.

In both Seattle and NYC’s cases, those laws also included a minimum earnings floor. However, the important distinction being that in those cities the pay formula was designed to account for time where drivers do not have anyone in their backseats. The time spent driving around aimlessly waiting for passengers — “deadhead mileage” in industry-speak — is a non-trivial amount of drivers’ overall work time. Obviously, Uber/Lyft would prefer not to pay their drivers for this time. As a result of Prop 22 passing, they won’t have to in California.

This is a classic case of regulatory arbitrage. The like equivalent would be UPS only paying their drivers for the time their truck is parked on the person’s street to whom they are delivering a package. To help reframe this for corporate office workers, what profit-maximizing company wouldn’t jump at the opportunity to compensate their employees strictly for the time their Excel spreadsheets are open on their computers? “Lunch? Lunch is for wimps!” as Gordon Gekko once quipped.

Prop 22 is less an indictment of the these companies’ avarice or greed than it is a wholesale abdication of sophisticated rule-making. California had close to a decade to figure this out. And, they had the benefit of the industry being birthed in their own backyard. Not to mention, there were already several city-level templates that established workable frameworks which were sitting on the shelf. Should regulators be upset that the companies beat them at their own game?

The Seductive Power of Convenience

How is that these companies were able to single-handedly write the terms of, validate voter signatures and solicit mass support for their own special legislation? Legislation which, by the way, requires a 7/8 (~88 percent) majority (!) in each chamber of the California legislature in order to make any meaningful changes to the law.

The power of unrivaled convenience.

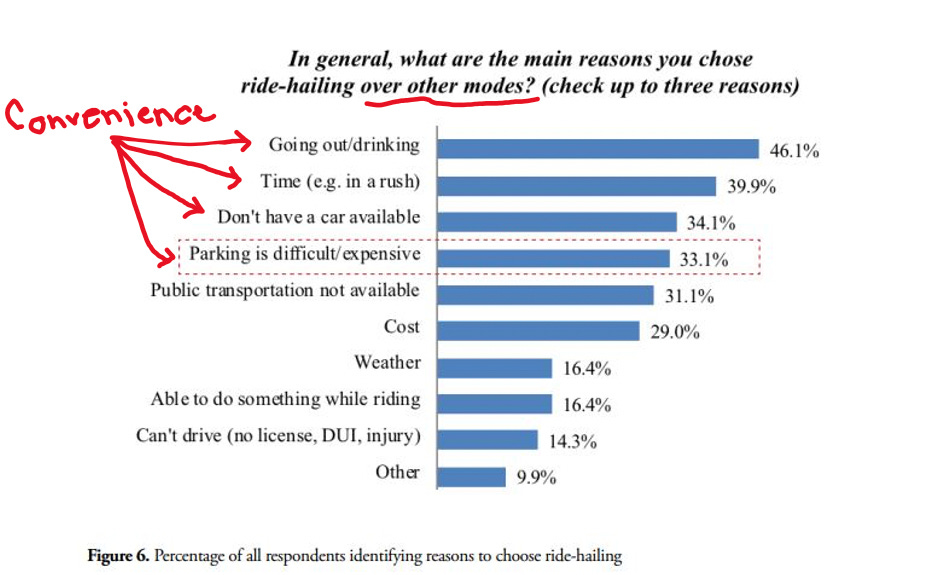

Source: Mobility Lab

“Convenience” is the secret sauce of mobility and is the aggregate lived experience of a user. It includes performance metrics including usability, reliability, latency, and affordability. When Uber/Lyft are able to flood cities with on-demand cars waiting in queue, they are able to check most of these boxes.

You will notice that I’m not talking about access to politicians (although that certainly is a contributing factor). Rather, Uber’s “power” is measured by its ability to exert a tremendous degree of influence via the cultural and behavioral shifts they’ve introduced to the general population. Before app-based ride-hailing came along, there were certain things people took for granted: taxi cabs which serviced high-demand areas at the expense of low-demand ones (which were usually poorer, devoid of transit options and disproportionately communities of color), driving drunk (because what else are your options?), walking but more frequently driving to a bus stop or train station in order to get somewhere else, and most importantly waiting for a train or bus to take you to that somewhere. These were the “frictions” of the modern day transportation experience circa 2009.

Uber’s former CEO Travis Kalanick understood these frictions perhaps better than anyone: as Mike Isaac wrote in his book Super Pumped, Kalanick was obsessed with making his app a completely “frictionless” experience. The “UX had to sing” and part of that required making it as easy as possible to simply walk out your front door, pull out your phone, tap a few buttons and watch with a God-like view as a little black car sped to pick you up at your present location.

From the consumer’s perspective, this was a massive upgrade (or what economists like to call an increase in “consumer welfare”). Even peripatetic teenagers could rejoice at the endless possibilities of not having to rely on their mom to pick them up from the mall anymore. Everyone knows this, but too frequently do journalists and other serious-minded people skip over this critical point as if it’s been this way since the fish climbed out of the primordial lake.

None of this is to suggest that Uber, Lyft or DoorDash spending truckloads of cash to sway voters had a negligible impact on Election Day. Although the efficacy of campaign dollars is notoriously difficult to measure (and likely not as big a deal as some would make it seem), I am not going to sit here and discount the fact that Uber still relies on all types of covert practices to sully people’s reputations (see: Veena Dubal), construct clever narratives, and convince their drivers (and riders) that the government simply does not know what they are doing.

In this respect, Prop 22 was just more of the same. The concerned parties went all out to ensure that every single Californian knew where drivers supposedly stood on the ballot. As Lyft’s Co-Founder and President John Zimmer was quoted as saying “Drivers 4-1 want to maintain their [independent contractor] status, want to maintain their flexibility.” Who would dispute a 4-to-1 ratio? However, I would argue that the success or failure of Prop 22 hinged on Californians’ comfort level with a service, and more specifically the way that service makes them feel.

Robert Moses, the infamous master builder of New York City, was notorious for threatening mayor after mayor and governor after governor with resigning from his post (of which he held many simultaneously). It usually worked. The reason why it was so effective was that Moses had constructed a meticulous narrative of who “Robert Moses” represented. For the bulk of Moses’ time as a city official (which was most of his adult life), most New Yorkers knew him as a champion of the public good. Moses racked up goodwill having built many public parks in a post-war city that was drowning in automobiles and desperate for green acres. When Moses wanted something done a certain way, he almost always got his way because he not only had the public’s backing, but also all of the city’s press including the venerable New York Times. The parallels to the modern-day ride-hailing companies are too rich to ignore.

Since the company’s founding, Uber has never hesitated to rely on its goodwill with riders, the same goodwill it derived from its awesome convenience. When you look at the statewide voting map from November 3, effectively the entire state of California voted for the status quo, albeit a marginally different situation for drivers. Why is that? Most Americans (Californians included) are perfectly okay with the status quo: they love the convenience of hailing a ride from anywhere and at any time.

Importantly, Uber was able to produce a disequilibrium of consumer expectations — what I’ll call the “Disequilibrium of Uber Expectations” — only through the good graces of venture capital funding. As Hubert Horan has written extensively, Uber’s popularity was primarily driven by the fact that Uber could show more availability at lower prices than traditional taxis could offer. None of that would have been possible without the mountain of funding courtesy of investors that allowed the company to flood cities with drivers waiting in queue.

Then, once a city’s constituents became used to the awesome convenience of that service, Uber could use that manufactured goodwill as leverage when regulators decided that its “driver-partners” were for all intents and purposes, just another taxi driver (albeit without a proper license, without sufficient damage or accidental injury insurance, without a criminal background check, and without any sort of safety or navigational training). This was referred to internally as “Travis’s Law”, or the idea that as soon as enough people experienced Uber’s service, they would hate to see it go.

Kalanick’s labeling city governments as being too cozy with the “taxi cab cartel” was the transportation world equivalent of the “Washington swamp”. It was a sweeping generalization that was only partially accurate and served to stoke a dichotomy of us-vs-them. In truth, the unit economics of urban car service were always plagued with issues that seemed to require some sort of public support and oversight.

Prop 22 was the affirmation of Uber’s well-constructed (and constantly reinforced) narrative: regulators don’t know what they are doing and as a result of their ignorance will end up nixing a service that everyone likes. We’ve seen this story play out again and again. In San Antonio, officials retracted a fingerprinting ordinance after Uber left the city in protest and in 2016, Chicago electeds squashed a proposed fingerprinting ordinance once Uber threatened to leave the city. In Austin, Uber permanently exited that market having lost a similar ballot initiative only to return having successfully lobbied the state government to overturn the city’s fingerprinting requirements.

Before New York City passed extensive regulations on TNCs, Uber successfully mobilized riders (and drivers) to oppose a cap on the number of vehicles. Using their app as a propaganda tool, riders were shown an apocalyptic version of “de Blasio’s Uber” where either no cars could be hailed or wait times exceeded 20 minutes. Importantly, the app included a direct link to email a prepackaged statement of opposition to NYC’s mayor and city council. Over a period of seven years and having accumulated reams of user data, Uber took the 2008 Obama campaign’s digital playbook and injected it with steroids. And it usually worked.

The Road Ahead is Long and Winding (and Fraught with Shareholder Confidence)

Today, Uber and Lyft have both produced massive increases in shareholder wealth, with recent gains correlated with the timing of the California referendum. As of this writing, Uber’s total market cap was valued at approximately $88 billion while Lyft was valued at approximately $15 billion. A day before Prop 22 passed, those numbers were ~$61 billion and $8 billion, respectively. That is, Uber’s market cap increased by roughly 44 percent while Lyft experienced a nearly two-fold increase in market value. You don’t need a CFA to see how investors viewed Prop 22 as a huge win for the ride-hailing companies.

Just to step back for a minute: These are companies that to date have not produced a single profitable quarter and consistently lose billions of dollars. If you want to experience cognitive dissonance on live television, tune into Bloomberg where analysts are frequently interviewed about the ride-hailing companies’ stock performance. There, you will find flowery discussions about a “path to profitability”. You might even hear current Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi talk about how “our EBITDA was much lower than Q1 and was on a good path”.

Think about that for a moment: a CEO of a publicly-traded company can go on live TV and talk about how his company’s losses were not as bad as the previous quarter’s losses and the financial press will report that as news! Khosrowshahi framed this as him living in the “real world” while the rest of the world was stuck in “accounting world”. I’m not sure if today’s professors adopted a new pedagogy, but every corporate finance class I ever sat in always emphasized a company’s P&L statement. In fact, there was a special kind of obsession over “profitability”.

I am not going to turn this into a financial analysis of Uber or Lyft’s P&L; Ranjan Roy over at Margins is much better at that kind of thing. But one cannot simply square the reality that Uber’s CEO is apparently living in and the reality the rest of us find ourselves in. How, for example, do we rationalize the fact that Uber and Lyft may very well continue to see huge stock appreciation (despite consistently reporting losses) and continue to provide the service everyone likes? That is, a service that provides relatively cheap on-demand rides with minimal wait times? It cannot do so forever.

The only way Uber/Lyft can eke out a “path to profitability” is through quasi-monopolistic pricing through regulatory arbitrage (as described above), consolidation (Uber subsumes Lyft in the most likely scenario) and higher fares. In the latter case, higher prices can only mean one thing: less take-home pay for its “driver-partners”. Already, this has been happening. In recent years, dependent drivers (i.e., drivers that work more than ~30/hours week) have complained of not being able to survive on driving alone. Reports of Uber/Lyft drivers living out of their cars is less an anecdotal outlier than it is a symptom of the gig economy: precarious work produces precarious outcomes.

So, where we find ourselves is a world where:

Uber/Lyft are generating lots of shareholder wealth as investors hinge on one of the companies becoming the “Amazon of transportation” (investor thesis); importantly, there cannot be a critical mass of detractors from said thesis, otherwise the house of cards folds;

Uber/Lyft’s riders generally approve of having access to ride-hailing services in their communities;

Meanwhile, Uber/Lyft’s drivers are increasingly disenchanted (despite the companies’ manufactured narratives) due to inevitable pricing pressures (i.e., Uber/Lyft raising prices to account for increased regulation, but also in order to demonstrate the coveted path to profitability);

Cities/states frequently run into opposition — most of which is genuine, but some of which is not — when attempting to regulate ride-hailing companies, primarily because of point #2;

Increasingly, ride-hailing rules are adopted at the *state* level as a form of regulatory preemption and more often reflect the interests of ride-hailing companies than the workers (California’s AB-5 being a glaring exception, although now moot). Statehouse politicians are far less sophisticated than city-level officials and are consequently easily captured by Uber/Lyft’s policy teams;

Collectively, points #1-5 suggest a new equilibrium (disequilibrium?) where investors fund loss-making companies which collectively provide a service that cities/states cannot adequately provide themselves, but which cities/states view as a net benefit to their constituents.

Do the above points then not imply the voluntary provision of a quasi-public good (point-to-point transportation), that involves sustaining an unprofitable industry in order to provide external public benefits? This starts to sound a lot like the building of “turnpike” roads in late 18th and early 19th century America. Turnpike roads were some of early America’s first large-scale infrastructure projects. In an effort to connect rural agricultural markets with the developing country’s cities, turnpikes were viewed as a Pareto improvement to get goods to market.

Importantly, as economic historian David Klein writes, turnpikes were almost entirely financed by private subscription to stock. Turnpike companies were legally organized like corporate businesses of today. Turns out, they were wildly unprofitable. Stock subscription was necessary to construct the road and essentially a means of paying for all of the knock-on benefits which the road conferred: lower transportation costs, stimulated commerce, and increased land values. These “indirect benefits” were a huge selling point for towns and cities considering building their own turnpikes.

Turnpikes were funded and built even despite most contemporary investors knowing these projects would produce at best marginal returns over the long run. As Klein writes, “average yearly dividends usually put the figure barely above zero”. Between 1805 and 1838, the turnpike boom produced more than 500 quality roads. How did so many roads get built despite it being a terrible investment? As Klein further writes, the growth of turnpikes was made easier by the fact that in early America, the “town” (and not the county or state) served as a central organizing principle for local decision-making.

There was a deep sense of communal pride and civic duty which pressured townspeople to participate in the construction of public works. The moral sentiments of the day helped override the free-rider problem common to most public goods. Obviously, the historical example of turnpikes is not without its incongruities to ride-hailing services: investors have reaped large returns on Uber/Lyft and ride-hailing companies are asset-light while turnpikes were capital-intensive. However, from a political economy perspective there are some interesting parallels.

Of course, the advent of modern financial markets enabled a lot more “investors” to participate in the growth of a company. Perhaps, had 18th century townsfolk had access to a Bloomberg Terminal, there would have been an even greater feeding frenzy on turnpike stocks. The key point here is that Uber/Lyft’s continued appreciation in market value is being driven less by expectations of future profitability (neither company has figured this out yet) and more by the fact that people apparently cannot imagine a world where a service like Uber/Lyft does not exist.

This is the Disequilibrium of Uber Expectations brought about by (artificially produced) unrivaled convenience. Whereas early America turnpikes produced measurable knock-on economic and social benefits, app-based ride-hailing companies have produced much-harder-to-quantify effects. Clearly, consumers benefit from on-demand cheap taxi rides. Uber and Lyft might argue how does one accurately measure (and generalize for the population) the economic value of an individual’s time savings? It’s a good question.

A Policy Path Forward

Today, as a result of the pandemic, cities and states find themselves in a pickle. The ripple effects of repeated stay-at-home orders and shunted mobility has contributed to business closures and a corresponding uptick in unemployment. One of the worst-hit parts of the economy has been the services sector under which Uber/Lyft drivers typically fall. This was a theme that was prefaced by the Prop 22 campaign. The argument went something like: “You’re going to take away our flexibility, AND you’re going to do it in the middle of an economic crisis?” Never mind that these workers benefited from an entirely novel stimulus package in which independent contractors were provided unemployment-like benefits (see: "PUA”), despite their employers having never paid into the system.

Even policymakers with the best of intentions may hesitate to crack down on an industry that is, at least superficially, providing avenues of employment during a pandemic-induced recession. Any legislation that could be framed as too onerous on ride-hailing companies now faces the very gusty political headwinds of mass unemployment and dwindling job opportunities. This comes on top of the well-oiled industry narrative that, at least when it comes to regulating TNCs, government does not know what it is doing.

California’s AB-5 was a very poorly written bill. In addition to Uber/Lyft drivers, it swept up basically every occupation that was not covered by traditional forms of employment: freelance journalists, lawn care services and even horse handlers. It’s the classic case of unintended consequences: write a bill that’s targeted towards a specific issue which gets lots of media attention and then suddenly find yourself dealing with multiple aggrieved parties (i.e., not accounting for tail risks). So, what’s preferable to applying a blunt instrument like AB-5? Being surgical.

New York City’s TNC industry did not collapse into a black hole never to return again once the Taxi & Limousine Commission passed its TNC rules in 2018. In fact, as Michael Reich, James Parrot, and Dmitri Koustas recently showed, in the first full year the new rules were in effect weekly driver pay increased 9% year-over-year. The aggregate pay increase for drivers in NYC was $340 million in 2019. At the same time, passenger wait times decreased! How is it that you can increase driver earnings in an industry that was previously beset by an oversupply of drivers and also improve efficiency through reduced wait times?

This is where we come full circle: the *utilization rate* appears to be a major contributing factor to NYC’s (and likely also Seattle’s) success when setting a minimum earnings floor. Despite Uber/Lyft’s protestations that tens of thousands of drivers lost access to their apps in the NYC market, the drivers which retained their access saw their earnings go up. At the same time, since the rules incentivize Uber/Lyft drivers to have passengers in their backseat, the companies likely adjusted their algorithmic routing to minimize the amount of time that drivers were aimlessly circling Times Square or lower Manhattan, as examples.

These efficiency gains are positive developments both for drivers (more money in their pocket) and riders (less time spent waiting to be picked up). Even more so than these, however, it’s a huge win for cities who (at least prior to the pandemic) were trying to tamp down on one of the worst negative externalities of TNCs: car congestion in the urban core. The initial data out of NYC would suggest that an appropriately designed pay formula can enable cities to tackle multiple issues simultaneously. As Ali Griswold wrote about Parrot and Reich’s pay standard proposal back in 2018 (emphasis mine):

The simple brilliance is this: Parrott and Reich aren’t proposing a flat cap on how many cars or drivers can be on the road. Instead they are putting the companies in control. Uber can still have as many drivers on the road as it wishes. But the less work each of those drivers has, the more Uber has to pay. Putting utilization rate as the denominator in the formula incentivizes companies to bring that value as close to 1, or 100%, as possible, lifting driver wages and likely reducing congestion by ensuring that New York City’s streets aren’t continuously overwhelmed by ride-hail vehicles.

What this shows is that there is a policy path forward for cities and states across the country. Uber/Lyft drivers don’t necessarily need a completely novel labor classification. Nor do cities/states need to treat drivers as traditional employees. By designing a pay formula that is not necessarily rigid, but dynamically capped according to the number of passengers looking for a ride (demand) and the number of drivers available (supply), it does away with the need for a more rigid mechanism like vehicle caps. At the same time, it penalizes Uber/Lyft for flooding the streets with idling vehicles and instead incentivizes the companies to become more efficient in their operations.

Some Concluding Thoughts

The story becomes even clearer as we learn that Uber is in the process of (or has already) divested from almost all of its other business lines: urban air mobility (Elevate), urban freight (Uber Freight), micro-mobility (Jump) and autonomous cars (Uber ATG). No longer can analysts point to these auxiliary businesses as complementary to Uber’s core business which is ride-hailing. Uber Eats has certainly reaped a pandemic-induced spike in revenues; however, once vaccinations begin en masse and people begin returning to some semblance of normal life, this segment will only shrink not grow.

Do you think most office workers (Uber Eats’ frothiest demographic) love spending 16 hours of their day every day in the same apartment? I don’t. Frankly, food delivery was never a very profitable business to begin with; charging 20-30% commissions proves that point. So, this will leave Uber with what it started with: an app-based taxi dispatch system or “technology platform” as Uber’s comms team is quick to correct you.

One of my all-time favorite shows is HBO’s Silicon Valley. The show does a great job of not only parodying the many ridiculous aspects of tech companies’ work cultures (“tech bros”), but also highlighting how companies rely on fanciful narratives to captivate their primary audience: namely, investors. The TV-show version “Making the World a Better Place” is a neat summation of real-life examples: “Ignite Opportunity by Setting the World in Motion” (Uber) or “Improve People’s Lives with the World’s Best Transportation” (Lyft) or my new personal favorite “To Grow and Empower Local Economies” (DoorDash).

While that last one may suggest that a food delivery app can deliver economic gains on par with Thomas Edison’s light bulb, these flowery mission statements are not copy-edited to be reflective of real life. Instead, they reflect an alternative reality propped up by inflated expectations and sufficient investor cash. Uber/Lyft will go as far as their investors take them. As former Uber policy “fixer” Bradley Tusk noted last summer: “For as long as investors are willing to buy whatever [Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi] is selling them... he's going to keep doing it, why wouldn't he?” Cities and states need not be dragged along for the ride.